My Dad called me “happy Sash,” which was ironic because I was never a happy kid. I was a worried kid, just like I’m a worried adult. My dad would say it often, “she’s a Happy Sash.” I think he wanted me to be happy because then maybe he wouldn’t worry. He was a worrier too.

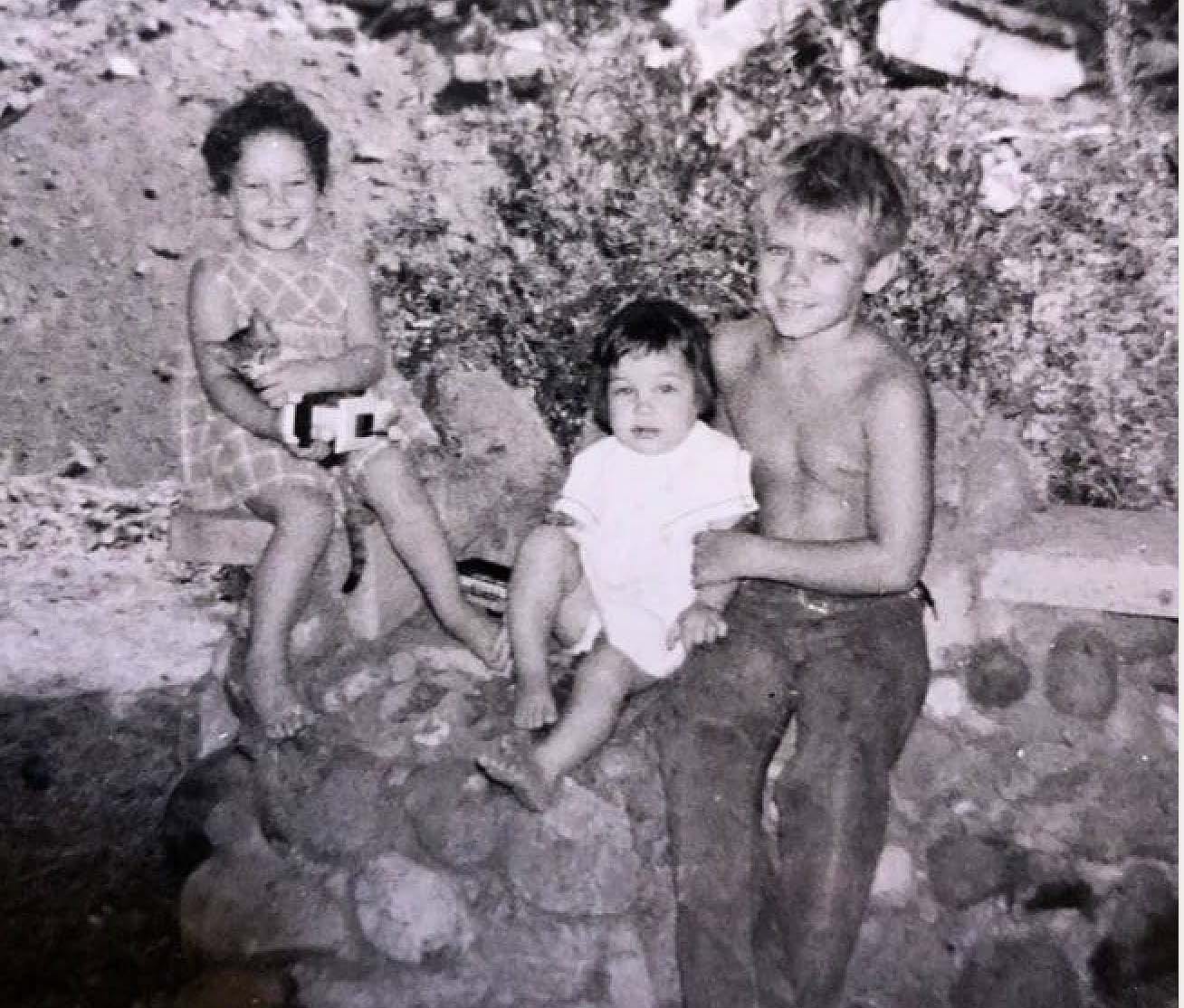

There aren’t many pictures of me as a baby, but here’s one. That’s me in the middle. As you can see, not exactly smiling.

When I think of my dad now, I think of the last year of his life. I drove down to the VA to see him every day. They had to keep moving him because he was a difficult patient. He was grumpy and sometimes flew into rages at the staff. He was a lifelong weed addict, and without it, he could not manage himself, which is why he stayed away from the hospital for so long.

I would tell you how we finally dragged him off to the hospital but trust me, you don’t want to know. It was too horrible. I would tell you about how my older sister had to try and rescue the cats he collected that never saw the light of day for their entire lives until she grabbed each of them as they hissed and spit and scratched her arm. Then they were sent to live with my mom, where they finally got a clean bed and sunshine on their faces.

My dad couldn’t really help it. He didn’t know how to live as a normal person. He could not manage himself or the house he inherited from my grandmother after she died. But he loved those cats more than anything. He loved one cat in particular, whose name was Freddy. He used to drive around with Freddy in his car. An easy-going Siamese my dad refused to neuter because he couldn’t imagine doing that to Freddy. So off he’d go into the neighborhood, producing untold litters of kittens.

When Freddy was hit by a car, it broke my dad. It was probably the most traumatic thing that ever happened to him, and considering his life, that was saying a lot.

My dad was raised by my grandmother, who was the eldest of a large family, and by the time she hit adulthood, all she wanted to do was become someone, yes, even back in the 1930s. She didn’t want to be stuck with a baby, and after her husband left, she sent my dad off to various boarding schools. He was an emotional wreck by the time they were through with him.

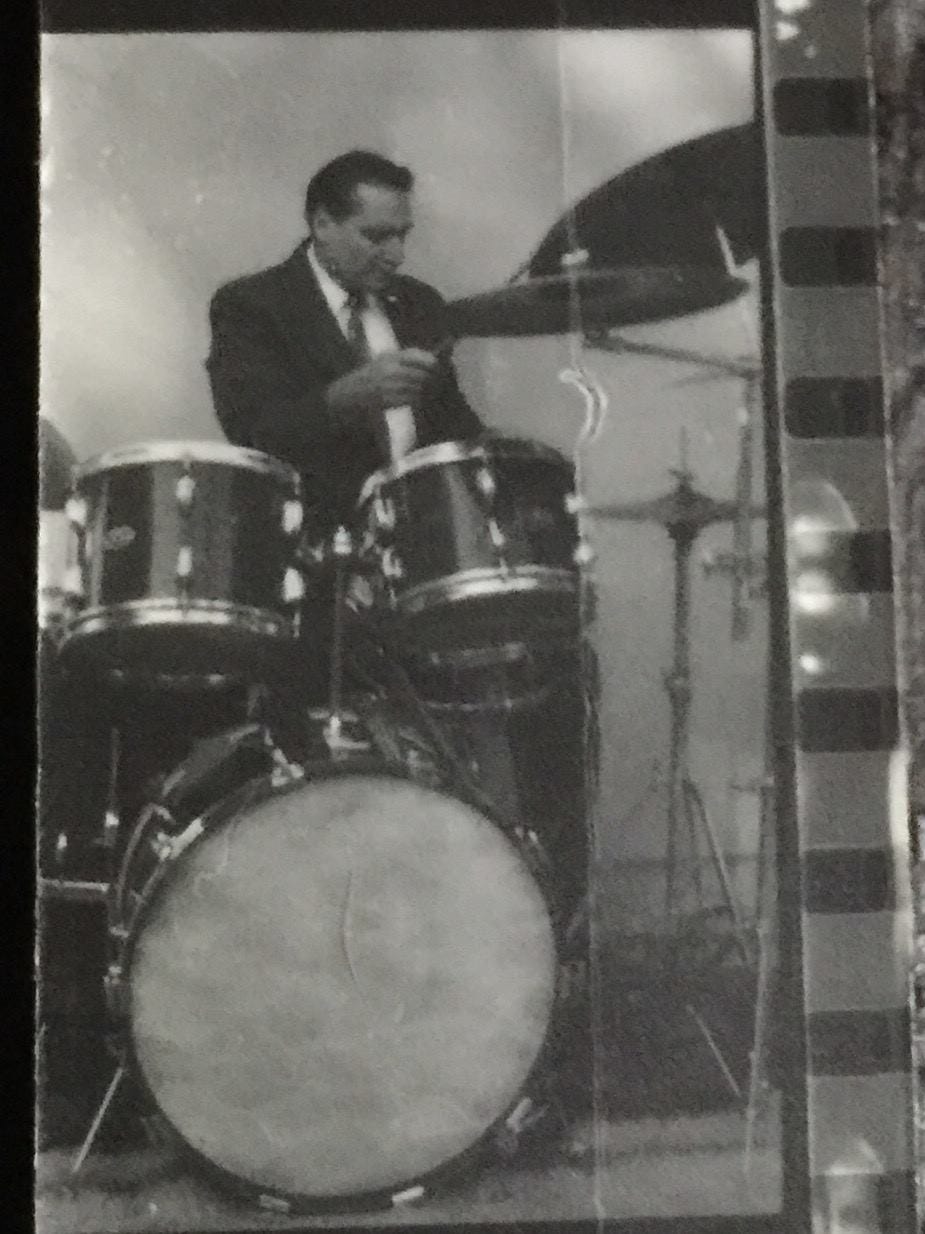

He became part of the gangs in Los Angeles and eventually found his way to Jazz. His father had been a well-known jazz musician who played in New Orleans. My dad began playing the drums and built a reputation for himself, slowly, even if another reputation trailed him, one he would never be able to fully shake, that he was “difficult” and probably “insane.”

My mother was 19 when she met my dad. “He had a Charles Manson-like hold on me,” she says now. They had three daughters together, all in a row. I am in the middle. My mom already had my brother, Scott, so they had four kids in their early 20s. In the 1960s. This was the days of hippies and the Hell’s Angels roaring through Topanga Canyon.

My dad was put in a mental institution, Camarillo State, and given shock therapy. My mother and grandmother had to rescue him from their care because they had turned him into someone who could barely speak. He was never quite the same after that, though he did his best to make his way in the world.

My mother resented him for the pain and misery he caused her, and still does. Her relationship with him is different from mine, and sometimes that’s hard to explain to her.

I loved my dad. I loved his sense of humor. It was absurdist and strange. Sometimes, out of the blue, he would just say a lizard. Or he’d say, a dog. Just the idea that these strange creatures existed at all was funny to him, and it’s still funny to me.

A lizard. A dog.

When I was raising my baby, my dad would bring over bags and bags of groceries. He would try to spend as much time with her, knowing there wasn’t a male figure in her life. As she grew up, though she appreciated his presence, he was almost always so stoned he would sit on the couch and watch TV. But you know how it is after people die, you miss even the things you used to complain about.

My dad built up a reputation as a great drummer. Anyone who saw him play knew that about him. I didn’t go see him enough, that’s the truth. I never fully appreciated jazz at all but especially not him playing it. Here he is, one of his drum solos I managed to capture:

The end was rough. When he got sick he was in denial about it. He’d had cancer but believed he’d cured himself through some kind of alternative treatment, so he didn’t trust the doctors when they told him he needed chemo.

While in the hospital, his musician friends came to visit to play with him. I brought him a drum pad and a drumstick to play one last time.

As he slipped into illness and dementia, we would watch movies together. I brought him an iPad so he could watch his favorite films, like Black Panther and Creed. I remember watching It’s a Wonderful Life and crying all the way through it.

In my dad’s last days, he said to me, in a rare moment of clarity, “I’m dying, aren’t I.” What he meant by that was that the denial finally caught up with him. I didn’t want to tell him he was and that there was no turning back, so I just said, “no, you just need to rest.”

On the day of his death, I’d gotten there five minutes too late. I was the first to find him. His chest was still warm. I was angry that he was sitting in a room full of bright light when all I’d asked them to do was to ensure the room was never bright. He hated that.

He was a military veteran, and when he died the nurse handed us a folded-up flag and said, “On behalf of the President of the United States, Donald J. Trump…” I remember bursting out laughing. That’s how crazy we were on the Left, how crazy I was. A moment that should have meant everything to me was turned into yet another justification to make a point about the election.

Of all of the things I think about now, all of these years after he died, that one somehow sticks with me. That moment. That even the death of my father couldn’t snap me out of my Trump derangement syndrome.

Moments after he died, my younger sister and I were in a screaming match about the election. “Bernie would have won,” she said. “Bernie is why we didn’t win!” I snapped back. My best friend finally had to pull us apart and say, “not in front of your father’s dead body!”

I have to now live with who I once was, and all of the cringe moments throughout my life. The one thing I don’t regret is spending my father’s last year of his life with him. He wasn’t a perfect father and was a barely functioning human being, but he was kind. He was there for me. So I was there for him. I can’t think of any way to spend my time that would have been more important than that.

I often wish he was still here because I do feel so alone so much of the time and the one thing I loved about my dad was that I could talk about anything with him and he’d mostly shrug it off and say, what are you gonna do.

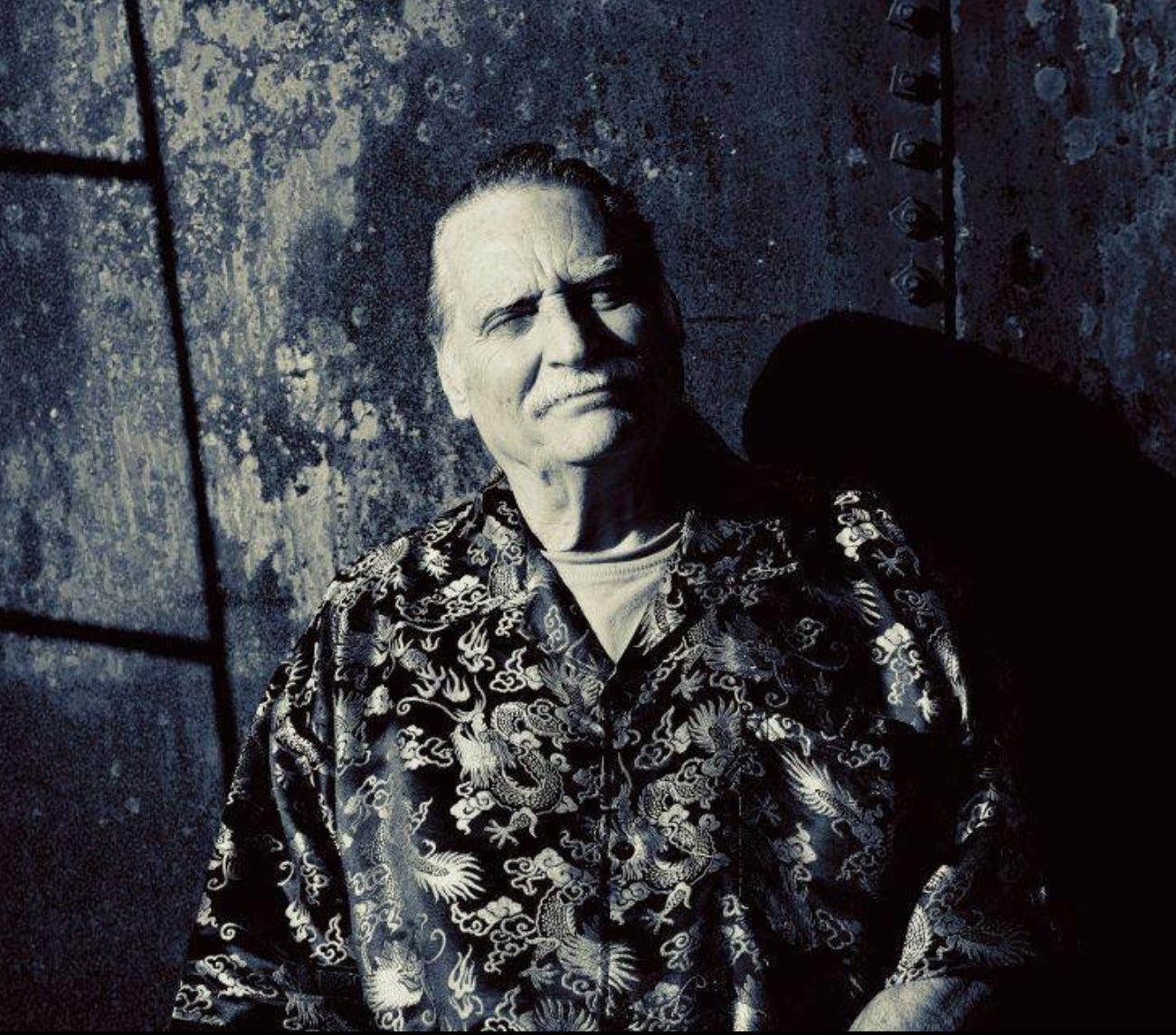

Rest in peace, my dear sweet funny gentle kind pops. I miss you every day.

Happy Father’s Day to all you dads out there.

Share this post